Blockchain-Scalability-Book

Chapter 2: The Blockchain Trilemma

Introduction

The blockchain trilemma is one of the most fundamental concepts in understanding the design constraints of decentralized systems. Coined by Ethereum co-founder Vitalik Buterin, the trilemma posits that blockchain networks can only optimize for two out of three key properties at any given time: decentralization, security, and scalability 1. This trade-off encapsulates the inherent challenges of building a blockchain that is simultaneously open to all participants, resistant to attacks, and capable of processing transactions at scale.

In Chapter 1, we explored the scalability gap between blockchain networks like Ethereum (~20 TPS) and centralized systems like VISA (~24,000 TPS). The blockchain trilemma provides a lens through which we can understand why this gap exists and why achieving all three properties—decentralization, security, and scalability—is so elusive. This chapter will break down each component of the trilemma, examine real-world examples, and set the stage for later discussions on Layer 1 and Layer 2 solutions that attempt to mitigate these trade-offs.

What Is the Blockchain Trilemma?

At its core, the blockchain trilemma is a framework that highlights the interdependent trade-offs in blockchain design:

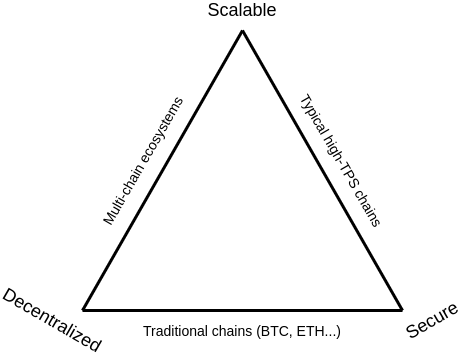

Figure 1: The Blockchain Trilemma - Decentralization, Security, and Scalability Trade-offs

- Decentralization: The extent to which a blockchain operates without a central authority, relying instead on a distributed network of nodes to validate transactions and maintain the ledger.

- Security: The ability of the blockchain to resist attacks (e.g., double-spending, 51% attacks) and ensure the integrity of its data and consensus mechanism.

- Scalability: The capacity of the blockchain to handle a growing number of transactions or users without compromising performance (e.g., throughput measured in TPS or latency).

The trilemma suggests that improving one of these properties often comes at the expense of the others. For instance, increasing scalability might require reducing the number of nodes involved in consensus (sacrificing decentralization), or enhancing security might slow down transaction processing (limiting scalability). This tension is not a flaw but a reflection of the unique constraints imposed by distributed systems—a departure from the centralized architectures of traditional databases 2.

Breaking Down the Trilemma

To fully grasp the blockchain trilemma, let’s examine each component and its implications.

Decentralization

Decentralization is the bedrock of blockchain technology, distinguishing it from centralized systems like PayPal or VISA. In a decentralized network, no single entity controls the system; instead, a global network of nodes collaborates to validate transactions and maintain the ledger. Bitcoin and Ethereum exemplify this principle, with thousands of nodes worldwide ensuring that no central authority can manipulate the system.

However, decentralization comes with a cost. Every node must process and store every transaction, leading to replicated computation and storage (as discussed in Chapter 1). This redundancy ensures trustlessness but severely limits scalability. For example, Ethereum’s requirement that all nodes validate every smart contract execution caps its throughput at ~20 TPS—a stark contrast to centralized systems that rely on a single, optimized server 3.

Security

Security in blockchain refers to the system’s ability to resist attacks and maintain the integrity of its ledger. This is achieved through consensus mechanisms like Proof of Work (PoW) or Proof of Stake (PoS), which ensure that malicious actors cannot alter the blockchain without overwhelming computational or economic costs. Bitcoin’s PoW, for instance, requires attackers to control more than 50% of the network’s hash rate—a feat that becomes increasingly expensive as the network grows 4.

Yet, security can conflict with scalability. PoW’s energy-intensive mining process slows down transaction confirmation times (Bitcoin averages ~7 TPS), while requiring broad participation to maintain decentralization. Reducing the number of validators to speed up consensus might boost scalability but could weaken security by making it easier for a small group to collude.

Scalability

Scalability, as defined in Chapter 1, is a blockchain’s ability to handle increasing workloads—more users, transactions, or smart contract interactions—without degrading performance. High scalability is essential for blockchain to compete with centralized systems and support applications like DeFi, NFTs, and global payments. However, achieving it often requires compromises.

For example, increasing block sizes or reducing block times can boost throughput, but this strains node resources, potentially excluding smaller participants and reducing decentralization. Alternatively, delegating transaction processing to a subset of nodes (e.g., in delegated Proof of Stake) can enhance scalability and maintain security but centralizes control in the hands of a few validators.

Real-World Examples of the Trilemma

The blockchain trilemma is not a theoretical abstraction—it manifests in the design choices of real-world networks. Let’s explore a few examples:

Bitcoin: Prioritizing Decentralization and Security

Bitcoin is designed to maximize decentralization and security at the expense of scalability. Its PoW consensus ensures robust security by making attacks prohibitively expensive, while its open network of nodes preserves decentralization. However, this comes at a cost: Bitcoin processes only ~7 TPS, and its 1 MB block size limits transaction throughput. Attempts to increase scalability (e.g., larger blocks) have sparked debates about centralization risks, as seen in the Bitcoin Cash fork 5.

Ethereum: Balancing Flexibility and Scalability Challenges

Ethereum aims for a balance between decentralization and security while supporting a versatile smart contract platform. Its PoW (pre-Merge) and now PoS consensus maintain security, and its global node network ensures decentralization. However, this design limits scalability to ~20 TPS, leading to high gas fees and congestion during peak usage (e.g., the CryptoKitties surge in 2017). Ethereum’s roadmap, including sharding and rollups (covered in later chapters), seeks to address this trade-off 6.

Binance Smart Chain: Sacrificing Decentralization for Scalability

Binance Smart Chain (BSC) prioritizes scalability and security over decentralization. By using a Proof of Staked Authority (PoSA) consensus with only 21 validators, BSC achieves higher throughput and lower fees than Ethereum. However, this small validator set raises centralization concerns, as a handful of entities control the network, potentially compromising its trustlessness 7.

Solana: High Scalability with Trade-Offs

Solana pushes scalability to the extreme, boasting ~4,000 TPS through its Proof of History (PoH) and parallel transaction processing. However, this comes with trade-offs in decentralization (fewer validators due to high hardware requirements) and security (network outages during peak demand). Solana’s design illustrates how aggressive scalability can strain other trilemma components 8.

Here’s a summary of these trade-offs:

| Blockchain | Decentralization | Security | Scalability (TPS) | Trade-Off Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bitcoin | High | High | ~7 | Sacrifices scalability for security |

| Ethereum | High | High | ~20 | Balances flexibility with limited scale |

| Binance Smart Chain | Low | Medium | ~100+ | Centralizes for speed and low fees |

| Solana | Medium | Medium | ~4,000 | High throughput with stability risks |

The Evolution of Exchanges and the Trilemma

The trilemma’s impact extends beyond blockchain protocols to the applications built on them, particularly cryptocurrency exchanges. The evolution from early trading mechanisms to centralized exchanges (CEXs) and later decentralized exchanges (DEXs) reflects the practical challenges of balancing decentralization, security, and scalability.

Early Days: Peer-to-Peer Trading

In Bitcoin’s early days (2009–2011), trading was purely peer-to-peer, conducted via forums like BitcoinTalk or IRC channels. Users negotiated trades directly, exchanging BTC for fiat or other assets off-chain, with transactions settled on the Bitcoin blockchain. This approach was highly decentralized—no intermediaries controlled the process—but it was neither scalable nor secure. Trades were slow, trust-dependent (risking scams), and limited to a small community, processing only a handful of transactions daily 9.

Rise of Centralized Exchanges

As Bitcoin gained traction, the limitations of peer-to-peer trading became apparent. Scalability demanded faster, more efficient systems, and security required protections against fraud. This led to the rise of centralized exchanges like Mt. Gox (launched 2010), which dominated early crypto trading. CEXs operated off-chain, matching buy/sell orders in a centralized database and settling trades internally, only occasionally interacting with the blockchain for deposits and withdrawals. This design sacrificed decentralization for scalability and security: Mt. Gox could handle thousands of trades per day with custodial security measures, far outpacing Bitcoin’s ~7 TPS. However, centralization introduced single points of failure—Mt. Gox’s infamous 2014 hack, losing 850,000 BTC, underscored the risks of trusting a centralized entity 10.

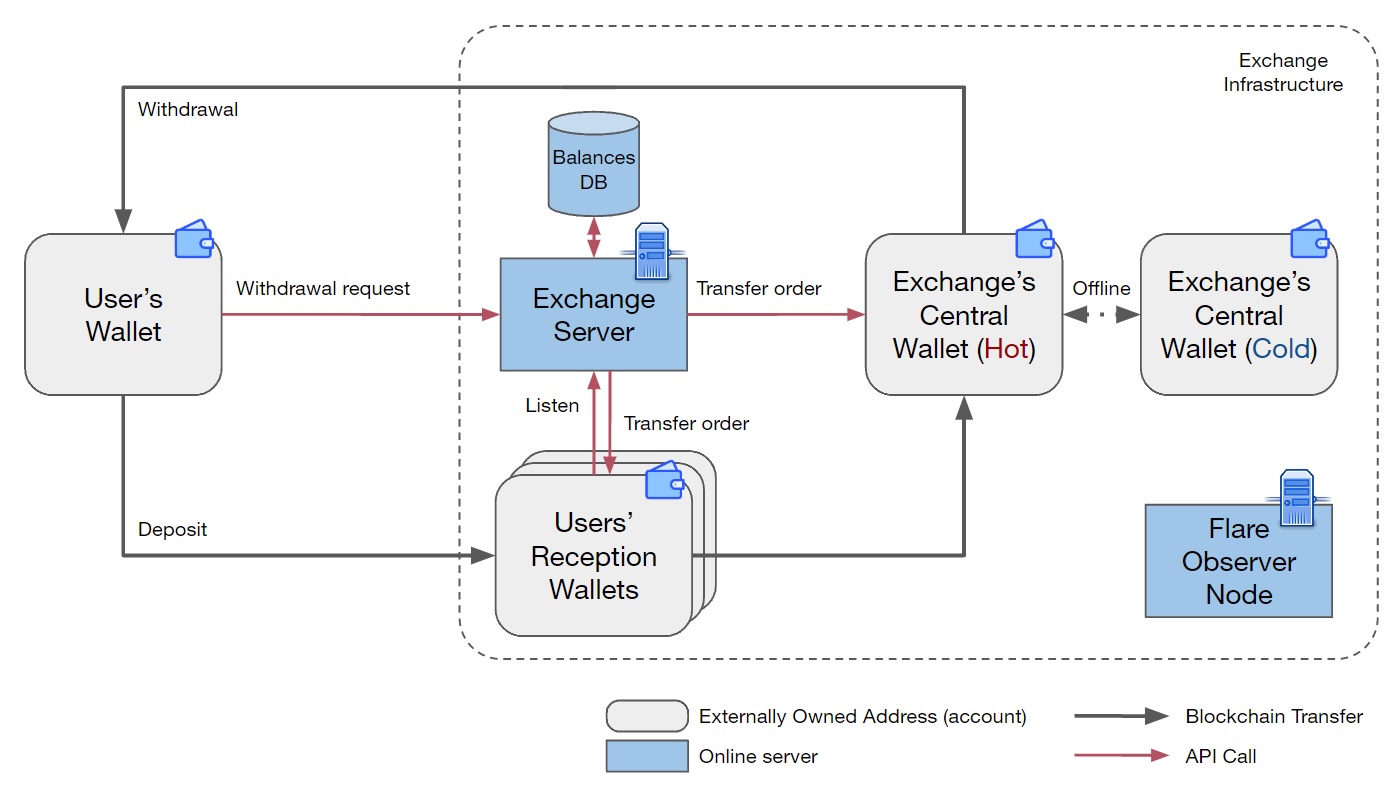

Figure 2: Centralized Exchange (CEX) Architecture

The trilemma explains this shift: Bitcoin’s decentralized and secure base layer couldn’t scale to meet growing demand, pushing users toward centralized solutions. Ethereum’s launch in 2015 amplified this trend, as smart contracts enabled DeFi but strained the network’s ~20 TPS capacity, driving traders to CEXs like Binance for speed and lower costs.

DEXs and the Scalability Revolution

Decentralized exchanges emerged to reclaim decentralization, leveraging blockchain’s trustless ethos. Early DEXs, like EtherDelta (2017), ran entirely on-chain using Ethereum smart contracts for order matching and settlement. While secure and decentralized, they were crippled by scalability: high gas fees and slow transaction times made them impractical during network congestion (e.g., the CryptoKitties surge). The trilemma was stark—on-chain DEXs preserved decentralization and security but couldn’t scale.

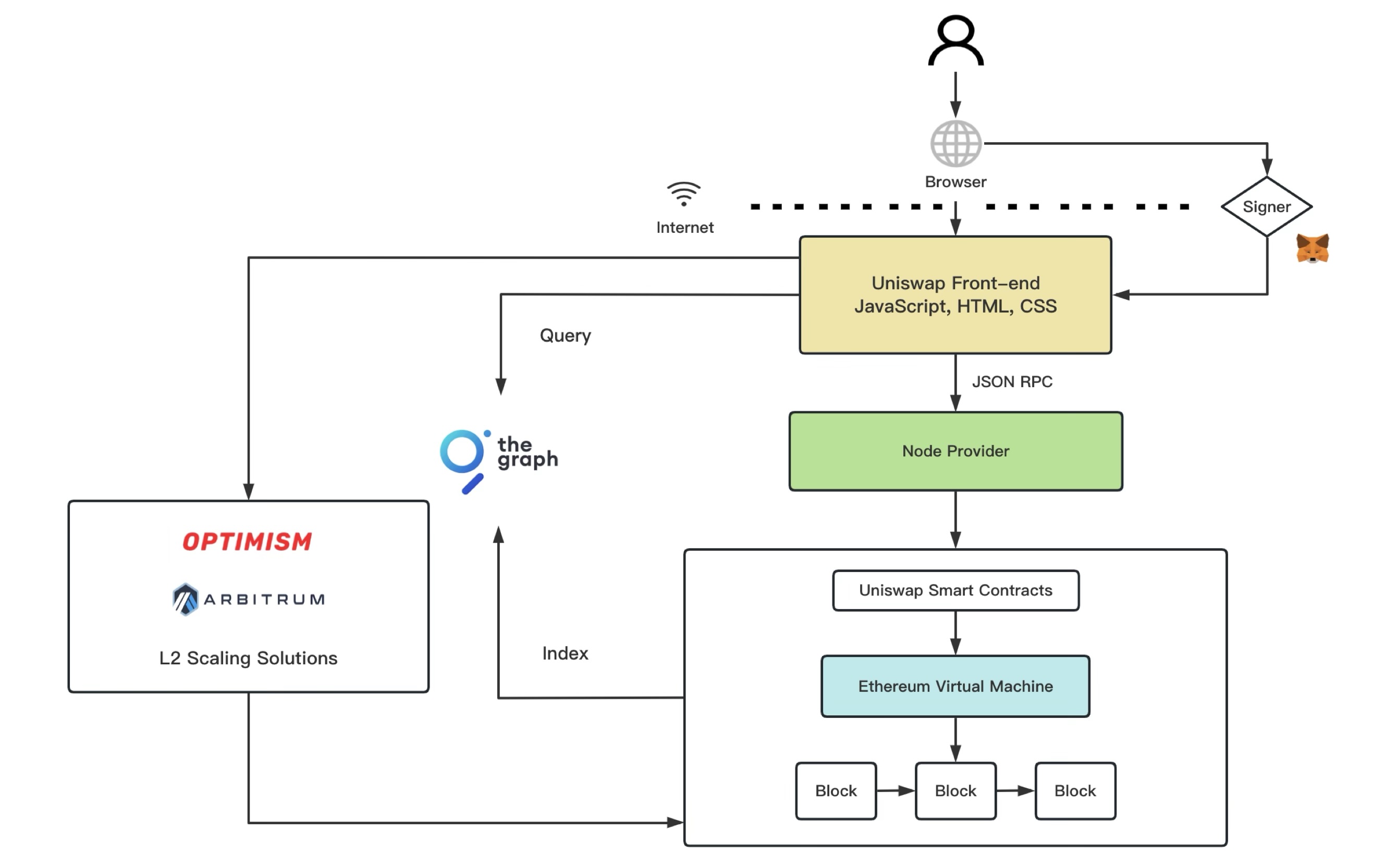

Figure 3: Decentralized Exchange (DEX) Architecture

The evolution of scaling solutions transformed DEXs. Layer 2 rollups (e.g., Optimism, Arbitrum) and high-throughput Layer 1 chains (e.g., BSC, Solana) enabled DEXs like Uniswap and PancakeSwap to process thousands of trades efficiently. Uniswap V3, for instance, uses Ethereum’s Layer 1 for security and decentralization while offloading computation to Layer 2 for scalability, reducing fees and latency. Similarly, Serum on Solana leverages PoH to achieve CEX-like speeds without sacrificing on-chain settlement 11. These advancements illustrate how scaling innovations mitigate the trilemma, allowing DEXs to compete with CEXs while retaining blockchain’s core principles.

Here’s a comparison of exchange evolution through the trilemma lens:

| Exchange Type | Decentralization | Security | Scalability | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Peer-to-Peer (Early) | High | Low | Very Low (~1 TPS) | Trust-dependent, slow |

| CEX (e.g., Mt. Gox) | Low | Medium | High (~1000s TPS) | Centralized, vulnerable to hacks |

| Early DEX (EtherDelta) | High | High | Low (~20 TPS) | On-chain, limited by gas fees |

| Modern DEX (Uniswap) | High | High | Medium (~100s TPS) | Leverages Layer 2 for scale |

The Trilemma in Context: Lessons from Traditional Systems

The blockchain trilemma echoes trade-offs seen in traditional distributed systems, such as the CAP theorem in databases. The CAP theorem states that a distributed system can only guarantee two out of three properties: consistency, availability, and partition tolerance 12. Similarly, the blockchain trilemma reflects the difficulty of optimizing competing goals in a decentralized environment. However, unlike databases, blockchains must also contend with Byzantine fault tolerance—resistance to malicious actors—which adds another layer of complexity.

Why the Trilemma Matters

The blockchain trilemma is more than a theoretical framework; it shapes the practical evolution of blockchain technology—including its ecosystems like exchanges. Understanding these trade-offs is crucial for:

- Developers: Designing systems that align with specific use cases (e.g., high-throughput payments vs. secure asset storage).

- Researchers: Exploring solutions that push the boundaries of the trilemma (e.g., rollups, sharding).

- Users: Evaluating which blockchains and applications meet their needs based on decentralization, security, or performance priorities.

For Ethereum, the trilemma underscores the urgency of scalability solutions. As a “decentralized world computer,” Ethereum must scale to support DeFi, NFTs, and beyond without losing its core principles. The CryptoKitties case study (Chapter 1) and the rise of DEXs highlight how scalability bottlenecks can ripple through the ecosystem, driving innovation to address these limits.

Beyond the Trilemma: A Path Forward

While the trilemma frames blockchain design as a zero-sum game, it also inspires innovation. Can we transcend these trade-offs entirely? Later chapters will explore approaches like:

- Layer 1 Solutions: Enhancing base-layer scalability (e.g., sharding, parallel execution).

- Layer 2 Solutions: Offloading computation to rollups while preserving security and decentralization.

- Modular Architectures: Separating consensus, execution, and data availability to optimize each independently.

These strategies don’t eliminate the trilemma but seek to mitigate its constraints, as seen in the evolution of DEXs, offering hope for a future where blockchains can scale without sacrificing their foundational values.

Conclusion

The blockchain trilemma encapsulates the core challenge of decentralized systems: balancing decentralization, security, and scalability. By dissecting this framework, we gain insight into why Bitcoin prioritizes security over speed, why Ethereum struggles with gas fees, why high-throughput chains like Solana face centralization risks, and how exchanges evolved from centralized hubs to scalable DEXs. As we progress through this book, the trilemma will serve as a guiding principle for evaluating scalability solutions and understanding their trade-offs.

In the next chapter, we’ll compare Layer 1 and Layer 2 approaches, building on the trilemma to explore how the blockchain community is tackling this enduring challenge.

Status: Work in Progress

Contributions Welcome: Feel free to expand this chapter with additional examples, diagrams, or research insights. See the Contributing Guide for details.

References

-

Buterin, Vitalik. “The Blockchain Trilemma.” Ethereum Blog (2017). Available at: https://vitalik.ca/general/2017/12/31/trilemma.html. ↩

-

Hill, Mark D. “What is Scalability?” ACM SIGARCH Computer Architecture News (1990). Referenced in Chapter 1. ↩

-

Wood, Gavin. “Ethereum: A Secure Decentralised Generalised Transaction Ledger.” Ethereum Yellow Paper (2014). Available at: https://ethereum.github.io/yellowpaper/paper.pdf. ↩

-

Nakamoto, Satoshi. “Bitcoin: A Peer-to-Peer Electronic Cash System” (2008). Available at: https://bitcoin.org/bitcoin.pdf. ↩

-

Hertig, Alyssa. “The Bitcoin Cash Fork: What It Means and What Happens Next.” CoinDesk (2017). Available at: https://www.coindesk.com/markets/2017/08/01/bitcoin-cash-fork-explained/. ↩

-

Buterin, Vitalik. “Ethereum Roadmap: Sharding and Rollups.” Ethereum Foundation Blog (2021). Available at: https://ethereum.org/en/roadmap/. ↩

-

Binance. “Binance Smart Chain Whitepaper.” (2020). Available at: https://www.binance.com/resources/BNB-Chain-Whitepaper.pdf. ↩

-

Yakovenko, Anatoly. “Solana: A New Architecture for a High Performance Blockchain.” Solana Whitepaper (2018). Available at: https://solana.com/solana-whitepaper.pdf. ↩

-

Narayanan, Arvind, et al. “Bitcoin and Cryptocurrency Technologies.” Princeton University Press (2016). ↩

-

McMillan, Robert. “The Inside Story of Mt. Gox, Bitcoin’s $460 Million Disaster.” Wired (2014). Available at: https://www.wired.com/2014/03/bitcoin-exchange/. ↩

-

Adams, Hayden, et al. “Uniswap V3 Core.” Uniswap Whitepaper (2021). Available at: https://uniswap.org/whitepaper-v3.pdf. ↩

-

Brewer, Eric A. “Towards Robust Distributed Systems.” PODC Keynote (2000). Available at: https://www.cs.berkeley.edu/~brewer/papers/podc2000.pdf. ↩